Childhood

Life’s Longing, Their Own Thoughts, Curiosity, Social Studies, Playhood, Baby Update (Personal)

Children of the future Age

Reading this indignant page,

Know that in a former time

Love! sweet Love! was thought a crime.

William Blake

I.

Life’s Longing

For this first idea, I’d like to share an excerpt from a maternity update I sent to family and friends earlier this year:

I was recently asked if I “felt connected” to the baby growing inside me. My honest answer? “Not really.”

While I feel immense love and motherly protection for baby Hana (as does Hunter), I don’t “feel connected” to her in the sense that I have any control over her. She kicks when she wants to, she rolls when she wants to, she’ll make her grand arrival when she wants to. And when she does, she will be her own person. While her body’s growth and development depend on me at this stage, it’s already apparent that she has a distinct spirit and reason for being that is entirely her own. We can’t wait to meet her and learn the lessons she will soon teach us.

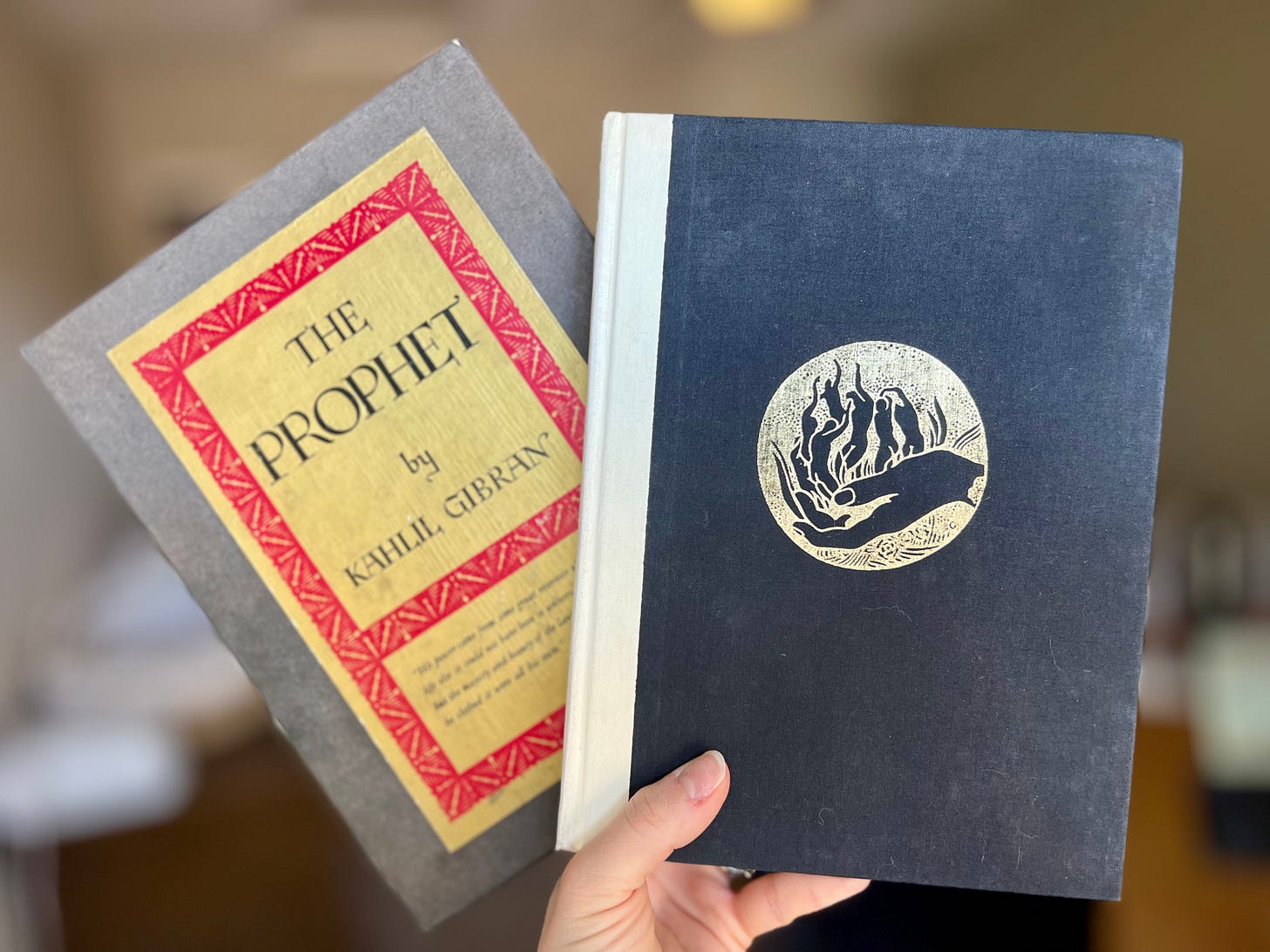

There’s a beautiful passage from Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet (1923) which captures this sentiment quite nicely:

II.

Their Own Thoughts

I found the following example in Stephen Cope’s The Great Work of Your Life (2014)

When you hear the name Jane Goodall, who do you think of?

Do you think of the chimpanzee lady? The conservationist? The humanitarian?

What about a curious little girl born into a wealthy family and living on a farm in the heart of London?

In her autobiography, Jane Goodall recounts a memory from when she was only four years old:

One of my tasks was to collect the hens’ eggs. As the days passed, I became more and more puzzled. Where on a chicken was there an opening big enough for an egg to come out? Apparently no one explained this properly, so I must have decided to find out for myself. I followed a hen into one of her little wooden henhouses—but of course, as I crawled after her she gave horrified squawks and hurriedly left. My young brain must have then worked out that I would have to be there first. So I crawled into another henhouse and waited, hoping a hen would come in to lay. And there I remained, crouched slightly in one corner, concealed in some straw, waiting.

Four-year-old Jane waited patiently for hours to see a hen lay an egg—something today’s kids might simply search on YouTube. But back at the house, the Goodall family was in a panic... Little Jane was missing!

The story continues:

At last, a hen came in, scratched about in the straw, and settled herself on her makeshift nest just in front of me. I must have kept very still or she would have been disturbed. Presently the hen half stood and I saw a round white object gradually protruding from the feathers between her legs. Suddenly with a plop, the egg landed on the straw. With clucks of pleasure the hen shook her feathers, nudged to the egg with her beak, and left. It is quite extraordinary how clearly I remember that whole sequence of events.

Little Jane Goodall vanished for several hours, sending her family into a desperate search. After witnessing the miracle of a hen laying an egg, she darted out of the henhouse, brimming with excitement to tell someone. When Jane’s mother spotted her, she rushed to her:

…despite her worry, when Vanne [Jane’s mother] saw the excited little girl rushing toward the house, she did not scold me. She noticed my shining eyes and sat down to listen to the story of how a hen lays an egg: the wonder of that moment when the egg finally fell to the ground.

As the daughter of a successful businessman and novelist, one might assume that Jane’s parents wanted their eldest daughter to grow up proper and polished. Perhaps become a professor or marry a nobleman. Instead, Jane was raised by parents who recognized, nurtured, and cherished her love for animals from a young age. While I would’ve been scolded for disappearing, Jane was celebrated for following her adventurous spirit—despite the unintentional stress it brought her family.

That support didn’t stop in childhood. Years later, Vanne would accompany her daughter into the Tanzanian jungle, “keeping hut” as her daughter launched her first field research station among the chimpanzees. And Jane’s father, Mortimer, gifted his baby girl a stuffed toy chimpanzee instead of the typical teddy bear—despite other parents warning that it would give her nightmares. Nearly 90 years later, Jane still has her stuffed chimp, named Jubilee, displayed on a dresser in her room.

III.

Curiosity

I recently came across a maternity update with the caption:

I’m just hopeful to have a little fishing buddy, boy or girl.

At one point in time, my Dad also wanted a “little fishing buddy.” But he ended up with four girls who get seasick and have no interest in baiting hooks or reeling fish out of the water.

It’s common for expectant parents to imagine who their child might become. Some want their little ones to share their passions and pastimes: A writer hopes her child will love books; an engineer pictures a mini tinkerer; a business owner envisions a future CEO in the family. While others set the bar even higher—hoping their kids will become doctors or lawyers or scholars or such.

But are we wanting the wrong things for our kids?

I think so.

What we should really want for our children is for them to be happy. And to be happy, they need to find what interests them. It’s unlikely their interests will align with our own, and we should consider it a blessing when they do. So rather than setting expectations for our little ones, we should strive to be like young Jane’s parents and seek to understand what makes our kids tick. What do they most want to discover about the world? What could they do for hours on end without tiring? What are their God-given gifts and talents?

As Kahlil Gibran writes:

You may give them your love but not your thoughts, for they have their own thoughts… you may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you.

Rather than pushing our dreams and desires onto our children, why don’t we let them show us their dreams and desires? Who knows, one day we may even want to be more like them when we grow up.

IV.

Social Studies

Obviously, a school that makes active children sit at desks studying mostly useless subjects is a bad school.

A.S. Neill, Summerhill (1960)

5 lessons from Summerhill, one of the most unusual schools in the world:

Inherent goodness: The greatest gift a child can receive is a life free from fear. The average child isn’t born timid, broken, or disinterested—they learn those behaviors from the adults around them. All children hold the potential to love life and discover their interests.

Happiness and wholeness: Education isn’t just about acquiring knowledge—it’s about helping children discover work that excites and fulfills them. A future vocation should engage the heart and soul, not just the intellect.

Emotional development: Learning isn’t just intellectual—it’s physical, emotional, and spiritual. Our fixation on academic success, while neglecting emotional intelligence, has left many disconnected from intuition, viewing life only through the filter of thought.

Individuality: Because children live in the present and have underdeveloped foresight, their education should reflect their current emotional and mental state and their abilities. Altruism and a sense of duty emerge after childhood—they shouldn’t be expected too early.

Mutual Respect: Respect must be mutual. Adults should never use power or force to control children, and children should not use force against adults. Respecting the autonomy of each individual, regardless of age, is foundational to freedom.

V.

Playhood

It is intriguing, yet most difficult, to assess the damage done to children who have not been allowed to play as much as they wanted to. I often wonder if the great masses who watch professional football are trying to live out their arrested play interest by identifying with the players, playing by proxy as it were.

A.S. Neill, Summerhill (1960)

In my last issue of 5 Big Ideas, I explored the importance of doing the inner work (i.e., “fixing yourself”) before bringing children into the world. Beyond the risk of passing on generational trauma or unhealthy patterns, there’s another quieter, but equally damaging consequence of unhealed adults stepping into parenthood: the inability to play.

From the very beginning of life, children need play. Babies need to be tickled and cuddled and smooched—not left alone in a motorized swing with a plastic toy. As they grow, play becomes even more essential to their mental, emotional, and physical development. It’s how they learn, connect, express themselves, and begin to understand the world.

Kids are wildly imaginative and unbound by adult conventions. One child might transform a cardboard box into a spaceship and blast off to Mars; another may fantasize a tale about bunnies bouncing on clouds. When we nurture children’s creativity—by playing alongside them, listening to their stories, and letting them lead—we give them permission to carry that lightheartedness into adulthood. We empower them to invent, envision, and create. Alternatively, when we treat play as a waste of time—crushing our children’s fantasies at home and eliminating unstructured free time at school—we hinder their ability to become free, fun, and forward-thinking adults one day.

When we ignore a child’s playfulness and tell them to “grow up,” we damage their spirit. And when these damaged kids grow up to be adults one day, they may find themselves living vicariously through others who know how to play rather than having fun themselves.

Pay it forward.

+I.

Baby Update (Personal)

Hana Evie ♥ April 6th, 2025