On Culture and Creators

Origins of Culture, Advertising & Media, Creator Economy, You Get What You Pay For, Big Bets

I.

Origins of Culture

Cultivation to the mind is as necessary as food to the body

Attributed to Cicero

The term culture finds its roots in the Latin word cultura, which originally referred to the agricultural practices of nurturing and honoring the land—tilling the soil, preparing the earth for crops, fostering plant growth. Agrarian prosperity was vital to sustain civilizations during the Agricultural Age1; thus, the land needed to be cultured.

Cato the Elder, author of one of the earliest surviving Latin prose works, De agri cultura, is believed to be among the first to use the word “culture” in a figurative sense, referring to the “cultivation of the mind”—cultura animi. Cicero later delved into themes related to cultivating the intellect through education and disciplined improvement in his philosophical writings. While the metaphorical usage of “culture” dates back to Ancient Rome, it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that the West began applying it to people instead of plants.

Today, the word “culture” is thrown around to describe all sorts of people things: pop culture, work environments, cultural diversity, social norms, humanities. So, when I read that Substack’s mission is to “build a new economic engine for culture,” my first thought was, “What kind?”

In recent decades, consumer culture has accelerated towards infinite distraction, the cult of influencers, political polarization, and ephemerality—a far cry from the philosophical ideals of cultura animi. However, now more than ever, there is an urgent need to nurture and honor our minds. Just as agrarian prosperity was vital during the Agricultural Age, intellectual prosperity is vital in the current Information Age.

II.

Advertising & Media

I came of age in the social media era: MySpace at 12, Facebook at 14, Tumblr at 15, and so on. But before my time, traditional media outlets (newspapers, radio, TV) were the primary gatekeepers of information and cultural content. Back then, media content was primarily characterized by centralized control, limited interactivity, and reliance on professional journalism and editorial guidelines.

While newspapers generated some revenue through subscriptions and newsstand sales, most traditional media relied primarily on advertising. This revenue model motivated traditional media companies to produce high-quality content to attract premium ad prices. For example, NBC could command a higher premium from advertisers for their hit TV show Friends compared to CBS’s Muddling Through, which lasted only one season (despite Jennifer Aniston starring in both).

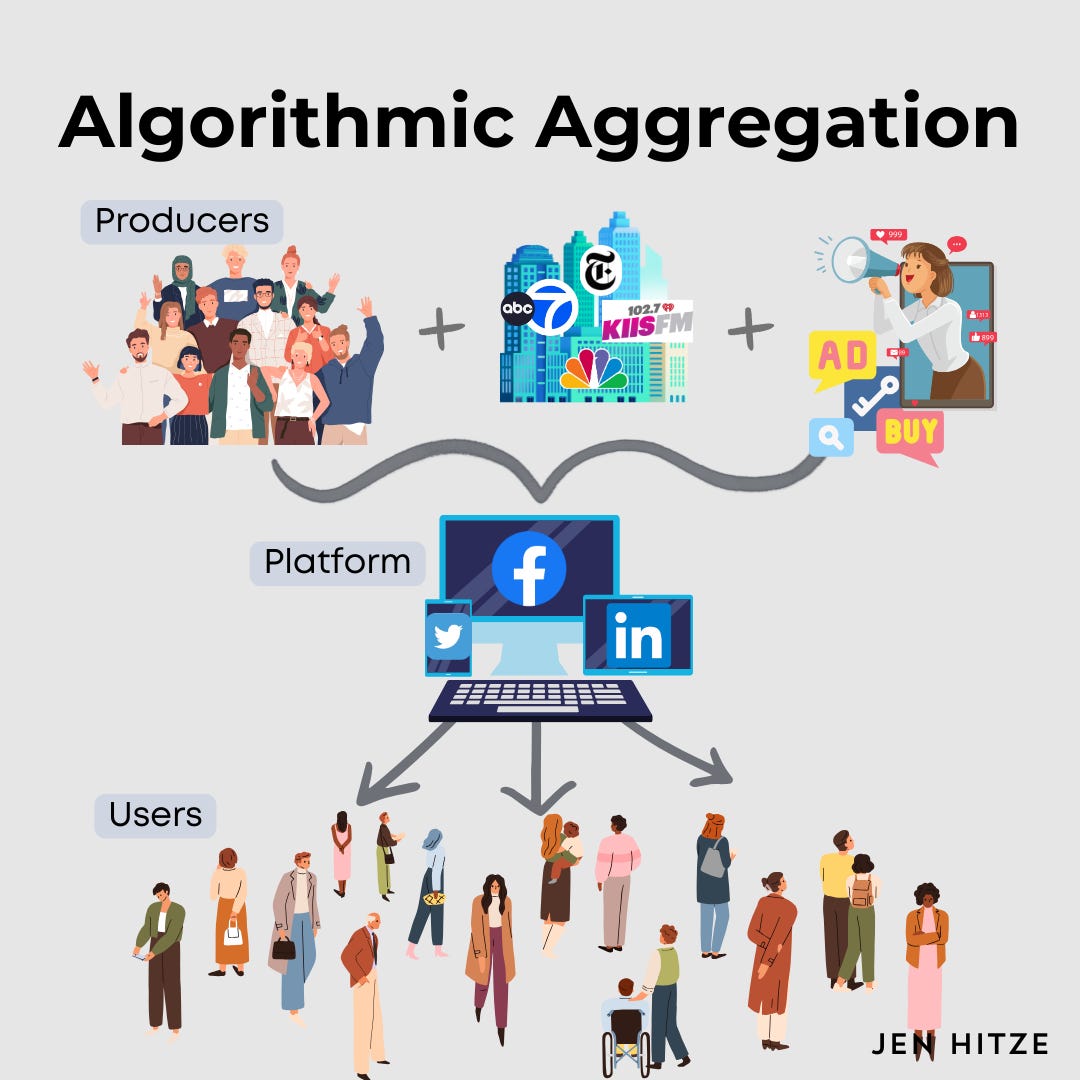

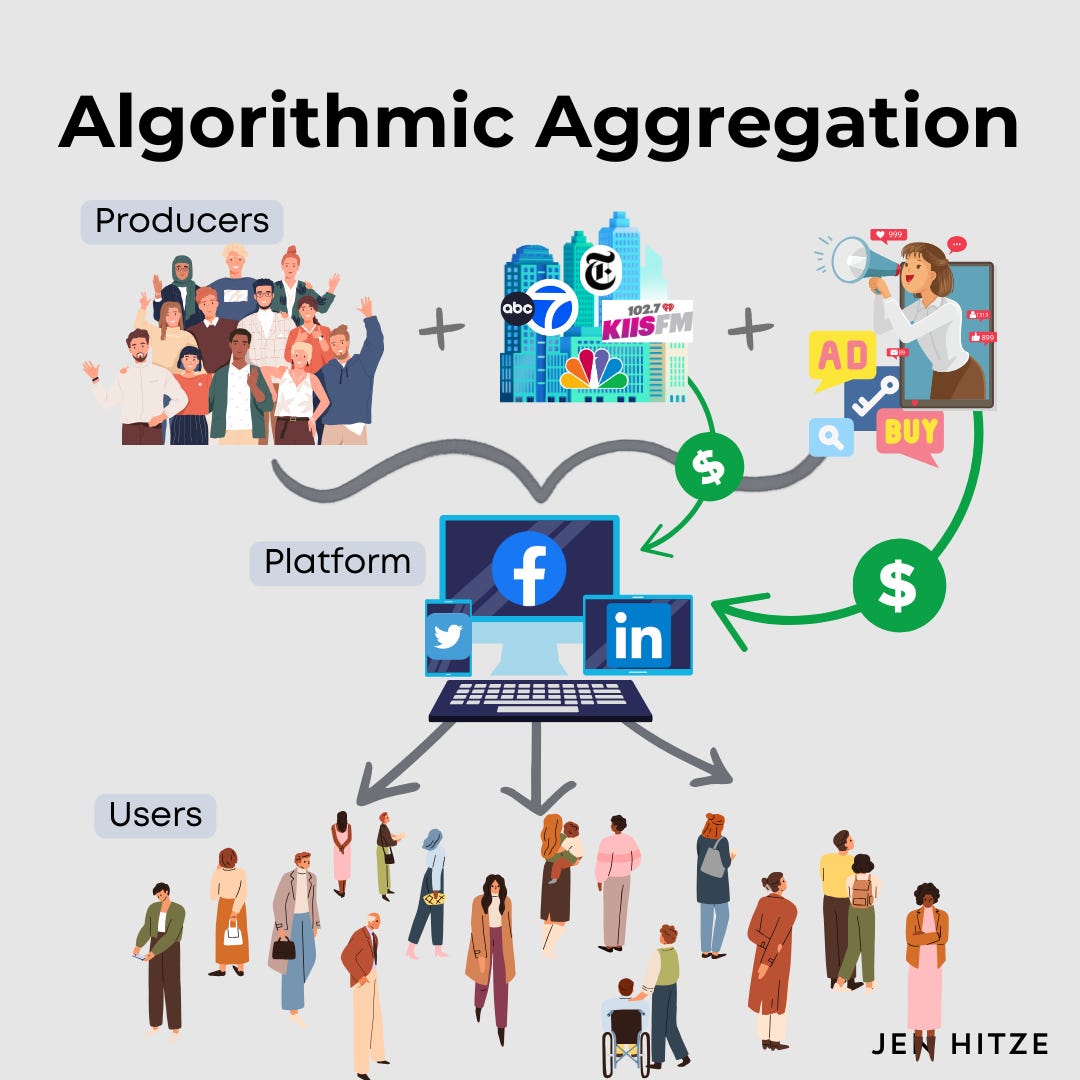

The emergence of social media disrupted these traditional dynamics. With social media platforms, users could personalize their newsfeeds, engage directly with content through comments and likes, and average joes could become content creators themselves. As social media reached widespread adoption, the volume of content available on popular platforms exploded. The platforms aggregated the overflowing media through an algorithmic funnel designed to deliver specific content to its users with the goal of keeping them on the platform for as long as possible.

While some social media companies generate revenue through user subscriptions (LinkedIn, 𝕏, YouTube), most platforms rely primarily on advertising. This aggregated advertising model prompted platforms to prioritize collecting as much user data as possible to command premium prices for hypertargeted advertising. As a result, the quality of content has suffered because the incentives have changed. Rather than striving to improve content quality to boost ad revenue, the goal became to enhance the efficacy of ads.

III.

Creator Economy

To keep our eyeballs on the newsfeed (and the ads), social media content devolved into a potato-chip version of its former self. Today, most content is empty calories; as Chris Best puts it, “Everything’s getting more compelling and less satisfying.” Personal updates devolved into self-promotion. Vlogs devolved into Shorts. Filtered photos devolved into unrealistic standards. Columns devolved into 280 characters (unless you pay for more). And like potato chips, we keep consuming more of it because it’s engineered to be addictive. The content is bad on purpose to make you click.

Cato and Cicero would likely recoil at the TikTok videos that dominate Western culture today. Cultura animi, or “cultivation of the mind,” is not only a process of intellectual refinement; it’s a warning. Our minds will cultivate whatever we ingest. Consume crap, grow weeds.

But a post-platform media culture is underway. Some call it the “creator economy.” Here’s what you should know:

During the social media era, average joe and his friends began producing content alongside seasoned professionals. The platforms granted them the ability to amass an audience of their own, and with the rise of digital tools, they too could create compelling content. However, two big issues remained: these creators weren’t directly compensated for their content2, and they didn’t own the relationship with the platform’s users. They relied entirely on the platform and its algorithms to reach and sustain their viewership.

Some smart joes realized the pickle they were in. They understood that the content they created held value, and they arrived at the same epiphany as Ted Gioia: “The algorithm is not designed to help me—it just wants to manipulate me for the platform’s benefit.” So they took matters into their own hands.

To control their own creative destinies, average joes began producing content off-platform and distributing it directly to their audience. When professionals like Matthew Yglesias saw that they too could own their distribution, they departed from their respective institutions to ride this new cultural wave.

IV.

You Get What You Pay For

The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden

From what I can tell, there are two main directions in which the creator economy is headed: the advertising route and the patronizing route.

The advertising route takes a page from traditional media’s book. In this model, the individual creator or creative team replaces the institution to become the producer and distributor of content. To command premium advertising rates, creators are incentivized to produce superior content and grow their audience.

While the advertising model shows promise, the problem remains that the creators’ primary customers are advertisers. Consequently, creators may be motivated to cater to advertisers rather than their audience, potentially leading to issues like self-censorship or biased content. In their landmark 1998 paper, Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine, which laid the groundwork for the creation of Google, Larry Page and Sergey Brin wrote, “Advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of consumers.” The same can be said of all advertising funded content.

To address this challenge, creators are increasingly turning to patronization. The patron model predates mass media and commercial advertising, with numerous creators throughout history (Shakespeare, Bach, Michelangelo, Molière + many others) relying on wealthy individuals to endorse and commission artistic pursuits. But with the advent of online distribution and payments, creators can now seek support from all of their audience members for a nominal fee instead of depending solely on wealthy individuals (who, like advertisers, can meddle in creative endeavors). The more patrons one has, the greater their ability to invest time and effort into improving their craft. Furthermore, because it’s affordable to support the work of others, content creators become patrons themselves. This dynamic fosters the circulation of big ideas within communities like Substack. And whether we realize it or not, creators and patrons in this new cultural atmosphere are fostering a much-needed media meritocracy, wherein ability and talent triumph. (I can’t think of a more professional metric than that, fellow joes.)

As of this writing, 51 patrons support 5 Big Ideas by paying for this newsletter. These patrons (and hopefully future ones) make it possible for me to produce content that I can only hope is intellectually stimulating and capable of germinating novel insights. I have full autonomy over the content I create and the tools I utilize, while you, dear reader, have control over the content you subscribe to. Should you ever decide that these ideas are not for you, you can “unsubscribe” using the link at the bottom of this email. Alternatively, you can provide me with feedback in the comments.

Regardless of whether creators in this emerging economy choose the advertising or patronizing route, content quality is improving. And it’s creating a better culture for everyone. As creators and consumers of content, we get what we pay for. And we can pay with either our money or our minds.

V.

Big Bets

This last idea comes from Chamath Palihapitiya:

In a world where consumer consumption is still more than 60% of global GDP, but traditional media is the least valuable it’s ever been, content creators are the new tastemakers - of opinions, ideas, truths and products. They are creating a seismic shift in how the demand generation for trillions of dollars of goods and services works. And it is very poorly understood - which is where the opportunity is. I will focus more and more of my time in the creator economy over the coming years as I see it as one of the most disruptive new trends that will be impactful in the future.

Chamath Palihapitiya, Social Capital’s 2023 Annual Letter

5 Big Ideas is a reader-supported newsletter and a labor of love. If you find value in these ideas, please consider supporting this publication.

Thank you for reading.

Fun fact: The phrase “culture vulture” originated in the 1940s to describe someone who’s “voracious for culture.” The expression peaked in 2007 and has been in decline ever since. Perhaps it could use a comeback.

The Agricultural Age lasted from ~10,000 BC until the emergence of the Industrial Age in the 18th or 19th century AD

Sometime around 1962 I was riding a bus in NYC and was looking at all the advertisiing placards around the perimeter of the ceiling. Something about them bothered me and I mused on that for days and finally it struck me like a bolt of lightening. They were all in the imperative. They were telling me what to do, and in some cases, when and how. For example, “Get the best mortgage rate available/” “Call now to reserve your place at the hotel of your dreams.” “See the new model at your favorite dealer. “ “Stay at New York’s finest….” “Pay no more than 10% down….” “Eat at Joe’s Diner” “Win a trip to wherever…” and you can think of many more such examples such as a slogan connected to a sports shoe that said, “Just do it!” And a take off on the cover of a business magazine, “Do it. Get Rich.” And from the world of fitness, “Beat the bulge.” And “Lose the flabby look.” The end result as I saw it was "Spend, Buy, Waste, Want, Borrow." And here's the rub.

Those were in direct conflict with what I had learned growing up. "Save, Use, Keep, Have and Give."

I wrote a post about it and will consider updating in light of your good analysis of our culture of conspicuous consumption before we are all consumed. Thanks, Jen!

This article reminds me of days when it was normal to see signs saying things like "you must be this high to take this ride". Similarly, I think you might need to be at least 40 to appreciate the changes in how media is supported.